Art Sets.

Exploded textiles

Print this setBy the Art Gallery of NSW

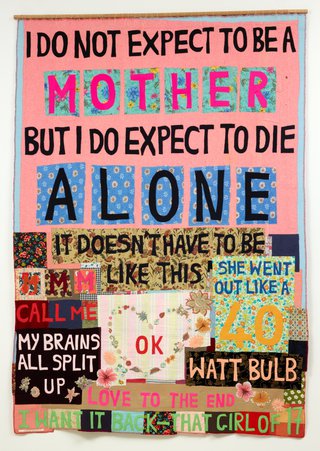

AGNSW collection Tracey Emin I do not expect 2002

Tracey Emin burst onto the British art scene in the early 1990s with raw confessional works that readily courted controversy. Her appliquéd tent Everyone I have ever slept with 1963–95 1995, has often been interpreted as a symbol of boasting sexual conquest, when in fact her list of people included a range of intimate, often poignant relationships such as that with her grandmother or with her own, aborted, children.

Public reaction to such autobiographical works peaked when she showed My bed 1998 – an installation of a sordid unmade bed – in the 1999 Turner Prize.

What they share with this work is Emin’s compelling use of textiles. Drawing from the legacy of feminist art, Emin amplifies the power of even ordinary everyday textiles like sheets and blankets to evoke intimacy. In I do not expect, she shows a fondness for subverting traditional handicrafts, particularly those made by women, giving them an altogether darker tone. The work was once described as a ‘cold meditation on the 40-year-old’s future’.

Emin continues many of the great humanist themes of Western art – the self, struggle, death – while recognising it has long denied the lived experience of women.

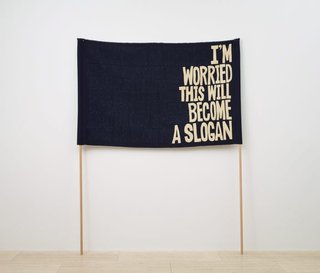

AGNSW collection Raquel Ormella I'm worried this will become a slogan (Anthony) 1999-2009

A keenly political artist, Raquel Ormella often works with the physical artefacts of social activism. She uses a host of diverse approaches and media, though textiles – with their rich cultural and material histories – often appear among her kitbag of signifiers.

I’m worried this will become a slogan (Anthony) and I’m worried I am not political enough (Julie) are from a series of banners Ormella made between 1999 and 2009. While they clearly mimic the form of protest banners, her modest handmade signs are presented in an art gallery, where any political efficacy is inevitably muted. They are both urgent and anxious, bold and somewhat pathetic.

The banners are two sided, on the other side of Anthony is the text: ‘“Anthony”, an Australian, has lived with Falintil guerrillas for 2 years. While he has not seen combat he is prepared to because “the world has turned its back on East Timor.”’ On the other side of Julie is the text: ‘Julia Butterfly Hill lived for 2 years in a 300-year-old redwood tree to stop it from being chopped down.’

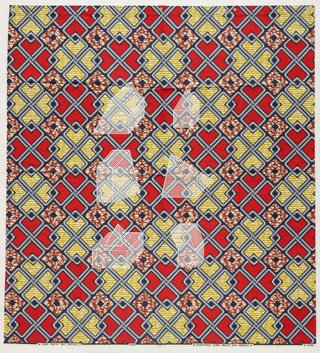

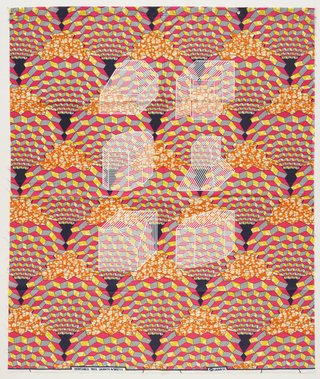

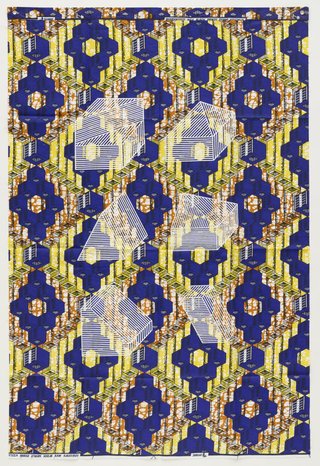

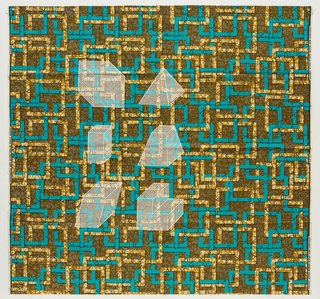

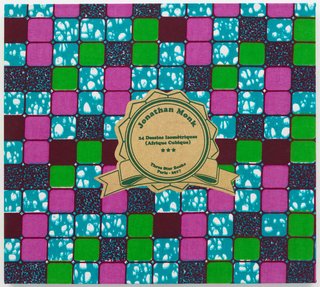

AGNSW collection Jonathan Monk 24 Dessins Isométriques (Afrique Cubique) 2017

For his 24 dessins isométriques – Afrique cubique, Jonathan Monk made four series of screenprints, each series with six different designs printed on different wax-print fabrics. A work from each series is displayed in the exhibition. They accompany an artist book – bound together like a textile sample book – which contains paper prints of the whole suite. Installed on metal eyelets, the large prints recall the way samples are displayed in a fabric store.

Monk often irreverently combines ideas and forms that are in apparent opposition. Here, he brings together two of his favourites: African wax-print fabric and Sol LeWitt’s Isometric drawings 1982. He takes from LeWitt – an influential pioneer of conceptual art – 24 of his isometric projections of forms and overlays them on the brightly patterned textiles. These fascinating fabrics have a complex history that reflects the convoluted movements of global trade played out over more than a century. While their inspiration and motifs began in Africa, the fabrics are produced in the manner of Indonesian batiks and they have been made in the Netherlands since the 19th century for the African market.

AGNSW collection Anne Graham Joni and Bacon 2014

Anne Graham moved from painting to textiles because she found she enjoyed the sculptural possibilities of canvas more than painting on it. Her mother was a tailor and Graham remembers being surrounded by the construction process that turned flat fabric into fully dimensional clothing. And she grew up in the north of England, a region once the heartland of Britain’s textile industry.

Today, Graham mines the history and associations of a range of evocative materials and objects. Her work explores questions of gender and labour and makes potent investigations into place and our relationship with nature.

Joni and Bacon and Julie and Cloud are part of a series of felt garments displayed alongside the photographs of her friends wearing the garments, with their pet dogs in tow. To make the outfits, Graham fused the owners’ dog hair with merino wool to make felt, one of the oldest known fabrics. Together, the garments and photographs establish a material connection between object and image, owner and pet. Joni Waka (Johnnie Walker) is director of a Tokyo-based art foundation; Bacon was his Irish wolfhound who died in 2008. Julie Rrap is an artist who investigates gender and the body. Her dog Cloud is a poodle.

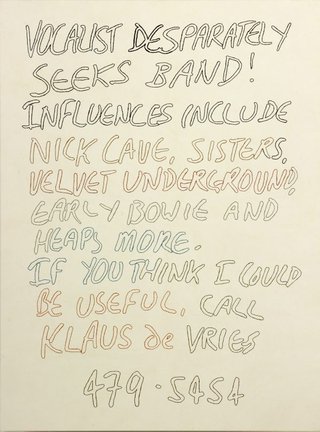

AGNSW collection Ronnie van Hout Vocalist seeks band 1995-1996

Ronnie van Hout’s work is diverse, shamelessly personal and often darkly absurdist. Theatrical and tragicomic, his work has been called ‘slapstick existentialism’. Not for him solemn, confident statements about the human condition. Instead, Van Hout summons the anxious and the paranoid, creating figurative sculptures (often of himself in some guise), videos and installations that turn up the volume on the ideas emerging in New Zealand contemporary art in the 1990s (something curator Robert Leonard named the ‘Gothic turn’).

Van Hout’s work draws heavily on pop-culture and everyday experiences. Vocalist seeks band may be more modest than his several public sculptures – one of which, Quasi, elicited calls for its removal from the rooftop of the Christchurch Art Gallery – but it is just as provocative. Here, when Van Hout embroiders a canvas with text from a band advertisement, he mixes the traditionally feminine activity of needlework with the testosterone-fuelled dreams of rock’n’roll stardom.

‘I can’t fulfil the promise of the previous generations’, Van Hout declared around this time, ‘so I am going to do silly, not silly, small things, small acts.’ In the small act of Vocalist seeks band, he brings together his trademark collision of humour and empathy.

Uploaded image

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Dale Frank Art and golden lies 1990, 1993.4

In late 1990, Tamworth City Gallery approached Dale Frank to select and respond to artworks from the collection in a bid to address the issue of regional audiences’ access to contemporary art. It was quite a radical proposal, especially given Frank’s reputation as a ‘bad boy’ artist, who seemed then to value transgression above all else. Frank – who was born in Singleton and lived in Scone – knew the collection well and Dale Frank vs the Tamworth City Gallery collection was born.

Art and golden lies was created in response to ‘traditional’ landscapes by Douglas Pratt and George Duncan, which Frank brought together (with a high-backed gallery chair) to form a new installation. In an interview at the time, Frank dismissed the notion of there being an end to traditional practice and a subsequent beginning of the contemporary.

Frank is considered by many to be one of Australia’s most important painters. He has always held that painting was ‘a form of conceptual art, and as such it must be judged, and hold its own, in relation to conceptual practices in other media’. In 1990, he was painting on carpets, bedspreads and ‘100% Australian wool (Onkaparingka)’ blankets – as well as beach towels.

Uploaded image

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Anita Larkin The breath between us (2014) 2016.2

Anita Larkin’s unlikely combination of laboriously handmade textiles and found objects seems to sharpen our focus on the relationship we have with things, memory, experience and language. Larkin describes her use of familiar objects – often chosen for their close contact with the human body – as a type of shorthand, instantly connecting us to broader and more complex issues in, and recollections of, the world.

Both Larkin’s collected and made objects are mined for the ideas they conjure: for their conceptual and symbolic resonances. To this she adds the associations of felt. Larkin enjoys not only the tactile and physical experience of making felt, but also its history as a truly ancient fabric (‘with one foot in our Neolithic nomadic past and one foot in industrial society’).

The breath between us was created for the second Tamworth Textile Triennial, which had as its theme collaboration. She made her outlandish musical instrument literally collaborative, requiring three people to play it. Felt is used for dampening sound inside musical instruments; here she pulls it to the outside to create an object with a felted heart and pair of lungs that sit directly over the player’s own.

AGNSW collection John Barbour Stopped clocks 1998

John Barbour investigated and revealed oppositions in physical material, space and time; playing with shifts between hard and soft, space and form. Textiles were an important part of his practice. Barbour deployed them to reveal their fragility, delicacy and capacity for movement – just as he worked often with metals to coax from them their properties of resistance.

Here lead – which also carries associations of alchemical transformations (from lead to gold) – is contrasted with a diaphanous fabric that carries its own connotations, from the seductive to the funerary. Soft yielding cloth and hard obdurate matter; these were the substances with which he worked.

Barbour recognised that all substances are in a constant state of physical decay and spoke about his practice as one of ‘unmaking’, connecting it to George Bataille’s concept of formlessness. He scrunched and folded his material, he painted using wet inks on wet fabric and revelled in the accidental mark, the stain and the trace.

Barbour’s works have been described as meditations on human frailty, failure and mortality. The title of Stopped clocks makes direct reference to a famous mourning poem by WH Auden.

Uploaded image

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Martha McDonald The weeping dress (2011) (detail) T2011.08 Photo by JM McDonald

Martha McDonald returned to live in America after some years studying and working in Melbourne. She activates her handcrafted costumes and textiles ‘through gestures, singing and autobiographical narrative’, in a practice that is often site-specific, connecting historic places with personal histories and emotional states.

The weeping dress – first performed at Craft Victoria, then at the first Tamworth Textile Triennial, in 2011 – arose from McDonald’s research into Victorian mourning rituals. Out of respect for the dead, women were not permitted to wear anything that would reflect the light during their first year of ‘deep mourning’. That meant wearing wool bombazine or crepe, which held plant-based dyes poorly, so that colour would run from the fabric in rain and heat, creating stains. In McDonald’s haunting performance, water poured over her as she sang, releasing the fugitive dye which streamed and pooled and left traces still visible in the performance artefacts.

McDonald recreated the labour-intensive handcrafts of mourning culture as a way of developing a language of performance and textiles that explored the longing for home she felt after three years in Australia, as well as ‘larger ideas of absence and impermanence’.

AGNSW collection Narelle Jubelin The unforeseen 1989

Narelle Jubelin has incorporated petit-point embroidery even in the largest and most complex architectural installations of her three-decade-long international career. Needlework has for her continued to be fruitful, rich with conceptual references and manifold assocations. Her use of embroidery complicates our reading and understanding of an artwork. Through it, she displays the skill of a traditionally feminine and time-consuming craft, while revealing it to be both object and image.

In the 1980s and 1990s Jubelin – strongly informed by feminist and post-colonial theory – stitched images of trade goods, historical monuments, old photographs and museum objects. She set them in found frames carved by amateur woodworkers, to ask questions about colonisation, trade, the circulation of objects and the ascribing of value – the domestic and hobbyist versus ‘high art’ traditions.

The unforeseen is shaped like an eye, its centre a ‘pupil’ formed from the image of a male figure about to enter a cave or mine. The title implies an element of risk (in exploiting the earth, in looking?). Jubelin offers us a kind of monument to male enterprise, but one she has reinscribed within a miniaturised, feminine framework – and one that offers us a warning.

AGNSW collection Rubaba Haider The spider's touch, how exquisitely fine! Feels at each thread, and lives along the line (Alexander Pope) IV 2017

Rubaba Haider is a Hazara woman who now lives in Melbourne, having fled first Afghanistan and then Pakistan as a result of ethnic persecution. Historically, Hazara women were expert weavers of rugs, and girls were expected to master the techniques of sewing, knitting, stitching and weaving. As she got older, Haider resisted learning these imposed skills and turned instead to painting. But threads, fabrics and needles continued to be potent symbols for her, signifying wounds, tears and community upheavals. She speaks of ‘unravelling threads’, knots and needles, mending and sewing, as metaphors for human relationships.

Haider studied traditional miniature painting in Lahore, but today seeks to redefine its conventions – as well as those of weaving and embroidery. She uses her virtuosic skills to evoke trauma and healing. Her meticulously rendered threads and stitches stand like scars, while rent fabric evokes memories of wounds and of communities torn apart by violence and warfare. And while she speaks of the fragility of relationships, she also reminds us that a mere thread can bind everything together: ‘I like the way the fabric could represent relationships … the way it stretches and strains but still holds together.’

Uploaded image

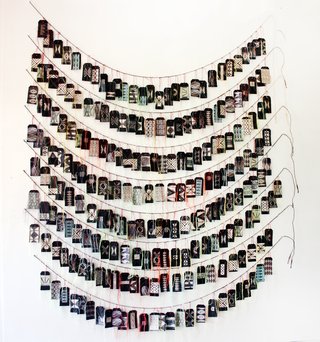

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Penny Evans Stranded (2014) 2014.5

When Penny Evans made Stranded in 2014, she declared its 226 pieces served to represent the 226 years since the colonisation of Australia in 1788. As the artist explains, each piece is made of printed cards featuring various diamond designs repeated from earlier ceramic-tile works with sgraffito (scratched) patterns. The cards were then stitched through a sewing machine. Evans explains that her trademark use of the ceramic scratching technique celebrates, ‘Gamilaroi traditions of carving into trees, weapons, utensils, emu eggs as well as ground carving for ceremonial purposes, communications and storytelling.’

Ultimately, each piece signifies people: some children, some elders, and others in various stages of initiation; each represented by designs and different thread colours. The eight strands of string signify eight skins: ‘cut threads hanging from every piece are a metaphor for the severed relationships to culture, family and land.’

Evans has further explained: ‘My Gamilaroi grandfather Bruce Maurer was an undertaker for much of his life and the diamonds traditionally signified burial. My pieces represent spirits from our Gamilaroi tribe who died in the frontier wars and were never given a proper burial. This is a memorial to those people. A symbolic gesture of recognition to those suspended or stranded spirits.’

Uploaded image

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Linda Lou Murphy drawing threads (2004) 2014.27

‘Drawing threads points to the transformative power of the passage of time and its carriage. A series of bags; hand, evening, vanity, tote, and bum, are combined with garments; gloves, mouthguard / gag, hat, apron, and bustle. Fabricated with paper and rendered with pins and stitches, the artefacts performed into being transform / contain / spill / disclose. Paper / skin / artefact / body are interchangeable.’

So wrote the late Linda Lou Murphy when she first performed drawing threads at Tamworth in 2004. What is missing, of course, from drawing threads in its 2019 iteration – and indeed from Murphy’s own written words – is the performative element that brought her work to life. The body was her crucial medium and material – both when working solo and as a member of the Adelaide collective shimmeeshok.

Yet the intricately pleated fragile objects Murphy made painstakingly from paper and dressmakers’ pins are more than mere documentation, or props. They are compelling sculptures that underline Murphy’s preoccupations with the body and its constraints. Murphy said that in this work ‘the gloves refer to the ideas of service, duty, etiquette, restraint and the demands on women in … family life in my history’.

AGNSW collection Regina Pilawuk Wilson Syaw (Fish net) 2004

In the early 1970s, Regina Wilson and her husband founded Peppimenarti, in the Daly River region of the Northern Territory, as a permanent settlement for the Ngangikurrungurr people. In 2001, she helped start Durrmu Arts and rapidly established for herself an internationally recognised practice.

Durrmu Arts states: ‘Wilson is a master weaver and colourist, who transforms her in-depth knowledge of colour, design and layering to set out the dimensions of a painting. From the tradition of her mother’s mother’s work, Wilson paints an extensive variety of stitching and weaving designs ... This painting represents the stitch and weave of the syaw or fish net. The weaving method is the same as the stitch used in weaving the warrgarri (dilly bag), except bigger. The pinbin vine (bush vine) grows near the river and is stripped into fibres which are then woven into the net. The syaw is used to catch fish, prawns and other edible creatures in the creeks and rivers.’

With Syaw (Fish net), Wilson replicates the elaborate and delicate patterning of woven objects that are very much a part of her continuing cultural and creative practice. Her particular innovation was to represent those cultural objects on canvas.

Uploaded image

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Julie Gough Navigator (2006) 2007.1

‘An expression of memorial to our (Tasmanian Aboriginal) Old People, Navigator physically renders the journey through time we all make in passing. Whether by underworld, river crossing or star system this canoe is a reminder of the various original belief systems that have provided a sense of comfort and direction for being and belonging. These craft best present my preoccupation with recreating passages about spaces beyond the material realm. Canoes, rafts, boards and other floating forms have … increasingly manifested in my work … as ways by which to travel through time and space. I made this work to honour the proximity of life, culture, memory, particular places in Tasmania and the past in my present.’

Julie Gough’s eloquence is often brought to bear on the violent colonial processes of annihilation that impacted her family’s Tebrikunna country in Tasmania’s north-east.

The canoes – constructed in part from blankets, crucial items of both trade and survival in the early days of settlement – refer to those in the 1807 image Terre de Diemen, navigation, vue de la côte orientale de l’Ile Schouten by French artists on Nicolas Baudin’s expedition to Australia. Gough collected the shells from beaches in her homeland.

Uploaded image

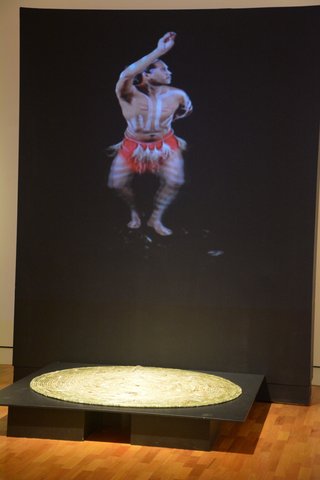

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Gomeroi Yinarr Amy Hammond and others Dhinawangu Walaaybaa (Emu’s Nest/Home) (2016) 2017.05

Weaver: Gomeroi Yinarr Amy Hammond

Singer: Gomeroi Murri Marc Sutherland

Dancer: Gomeroi Murri Brad Flanders

Dhinawan (Emu) has always lived on Gomeroi Country, our culture teaches us about their deep connections and our responsibility to look after them. In our Communities we share Dhinawangu garaygalga (Emu stories) and teachings in many ways, including weaving, kinship, yarning, dancing, painting, song, walking Country and looking in the night sky.

Weaving has been a part of Gomeroi Country since Creation and it has the power to hold deep cultural energy and stories. My weaving shares culture and truth telling, a reflection of the times. I cannot share the beauty and strength of Dhinawan with you without acknowledging their genocide.

The last 200 years of colonisation have seen Dhinawan massacred, forced off Country and its walaaybaa destroyed by the expansion of western progress, agriculture, early government culls and invasive species. The Tamworth Region continue to benefit from Dhinawangu genocide and it is executed as business as usual in 2019.

My woven lomandra mat and the Dhinawangu feathers represents the nest and home of Dhinawan on Gomeroi Country, the dancer Gomeroi Murri Brad Flanders is Dhinawangu spirit who is a bubaa (father) taking special care of their eggs and nest and the song by Gomeroi Murri Marc Sutherland is Dhinawangu song that we sing for them.

This work shares garaygalga (stories) of Dhinawan and is dedicated to the lives lost and that continue to be lost through colonisation.

Uploaded image

TAMWORTH REGIONAL GALLERY COLLECTION Lucy Irvine Continuous interruptions (2011) 2012.1 Photo by Lou Farina

When Lucy Irvine came to Australia in 2003, she developed her weaving practice in part as a means of orientation within an unknown landscape. Irvine makes sculptures from ubiquitous – but often surprisingly aesthetically pleasing – synthetic materials such as nylon line, irrigation piping and cable ties. Indeed, it is her very juxtaposition of expansive organic forms with those industrially produced, utilitarian materials, that forms the exciting tension in her work.

Irvine weaves, she says, in tiny increments, ‘slowly accumulating each movement, alignment, each stitch of a cable tie or cord’. A pattern then emerges ‘as a tessellation: always in motion, in response … nuances of surface, skin, process and form.’ She continues: ‘The resulting sculptures articulate a tension between chaos and order or the known and as yet unknown. In this regard the process of making is not simply an articulation of ideas; it is integral to the development and realisation of those ideas.’

During her more recent research, Irvine has established a practice that seeks to combine different forms of knowledge to articulate both memory and experience of landscape: ‘a way-finding through weaving’. This has seen her gravitate towards a more textile-based discourse to orientate her practice.

AGNSW collection Justin Trendall Black square 2009

Justin Trendall makes the network of influences on his art practice his subject. He charts relationships between artists, curators, gallerists, architects and musicians according to their importance to him, drawing them together into delicate interwoven structures of text and line.

In Black square Trendall almost perfectly sums up a decade of influences on the Sydney art scene, creating an art history of a time and place. In that history are not only his contemporaries in Sydney, but also cannonical figures like Giotto or popular ones like Tracey Emin (an artist included in this exhibition). Trendall also references the history of modernism and monochrome painting, most conspicuously Kazimir Malevich’s revolutionary Black square (created in series, from c1915 to the early 1930s).

Trendall’s direct and metaphorical reference to textiles is important. His prints are on fabric, not paper, and the lines of connection, memory and association all form a web, like a slightly stretched and holey knit, suggesting the fragility yet flexibility of a well-worn cloth. Ultimately, his maps act rather like commemorative textiles do, recording for future generations the names of those who came before, those who made an impact.

AGNSW collection Mona Hatoum Bukhara (red) 2007

Celebrated artist Mona Hatoum was born into a Palestinian family in Beirut and now lives and works between London and Berlin. She often works with domestic objects – objects the West associates with the Arab world – addressing issues of displacement, memory, history and identity.

Bukhara (red) is a traditional oriental carpet similar to those that furnished Hatoum’s childhood home. It looks as if it’s in a state of disintegration, with large patches of the weave appearing motheaten or worn. These patches come together to form a world map, the land masses and continents created by Hatoum painstakingly plucking out the pile of the carpet.

The image she forms is known as a Gall-Peters map of the world. This type of map is a rectangular projection that plots all areas to have the correct sizes relative to each other. It’s a more egalitarian representation than the familiar image of the world drawn from a dominant, northerly perspective, and as such, Bukhara (red) feels unfamiliar. But like any equal-area projection, the Gall-Peters projection relies on distortion to achieve its form, revealing its own inaccuracies.

AGNSW collection M Ganambarr Large handbag 2009

Leading fibre-artist Mavis Ganambarr was born at Matamata outstation, and now lives at Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island). Though Ganambarr ‘found weaving’ in earnest when she was around 19, she was first taught to weave by her grandmother, Djuluka, when she was little. She also learnt a great deal from her father, clan leader Mowarra, a renowned bark artist.

Today Ganambarr, who grew up in the bush, passes on her knowledge of plants and their preparation and her sophisticated weaving techniques to the younger generation on Galiwin’ku. She says, ‘It’s important, so part of doing our art is keeping our country strong, so when new generations grow they know what to do.’

Ganambarr extended the ways she could express her ancestral narratives and identity by translating traditional forms and techniques into a host of different contemporary applications – baskets, armbands, handbags, necklaces – to sell to museums or tourists. But they remain cultural items, ones that assert her own enduring cultural values. They are, as writer Doreen Mellor put it, ‘at once important ceremonial objects, useful items and a way to engage with market forces.’